Carla Accardi Italian, 1924-2014

In Spring 2020, Carla Accardi (1924-2014) will be the subject of a comprehensive retrospective at Museo del Novecento, Milan (27 March – 30 August).

Her work has been featured in seminal group exhibitions including The Venice Biennale (1948, 1964, 1976, 1978, 1988, 1993); Italics: Italian Art between Tradition and Revolution 1968-2008, Palazzo Grassi, Venice, 27 September 2008 – 22 March 2009, Museum of Contemporary Art, Chicago, 18 July – 25 October 2009; Roma 1948-1959: Arte cronaca e cultura dal Neorealismo alla Dolce Vita, curated by Maurizio Fagiolo dell’Arco and Claudia Terenzi, Palazzo delle Esposizioni, Rome, 30 January – 27 May 2002; The Italian Metamorphosis, 1943-1968, curated by Germano Celant, The Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, 7 October 1994 – 29 January 1995, Kunstmuseum, Wolfsburg, 22 April – 13 August 1995; Italian Art in the 20th Century, curated by Germano Celant and Norman Rosenthal, Royal Academy of Arts, London, 14 January – 9 April 1989; Chambres d’amis, curated by Jan Hoet, Museum van Hedendaagse, Ghent, 21 June – 21 September 1986.

-

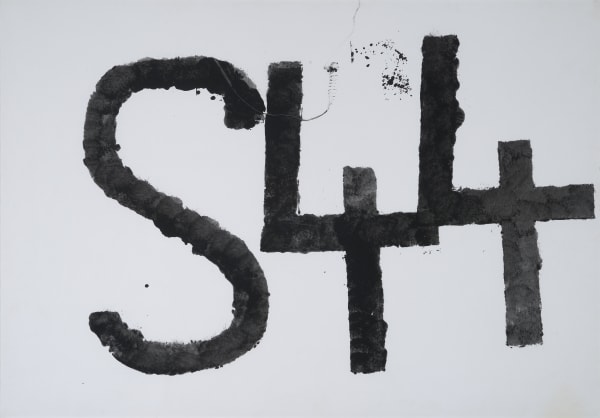

From Word to Sign: Accardi Basquiat Boetti Capogrossi Kounellis Novelli Perilli Twombly

curated by Maria Albani 16 Luglio - 30 Ottobre 2020MILAN - ML Fine Art - Matteo Lampertico invites you to discover our online exhibition focused on the relationship between painting and writing, showcasing selected works by Carla Accardi, Jean-Michel...Maggiori informazioni -

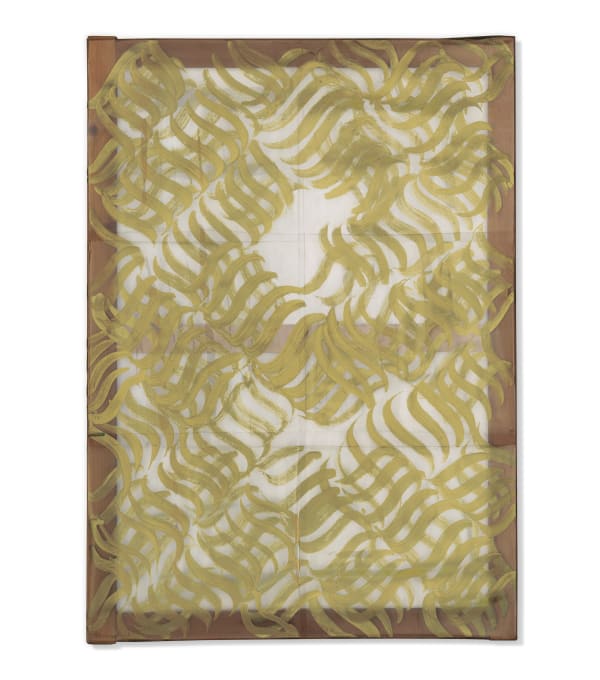

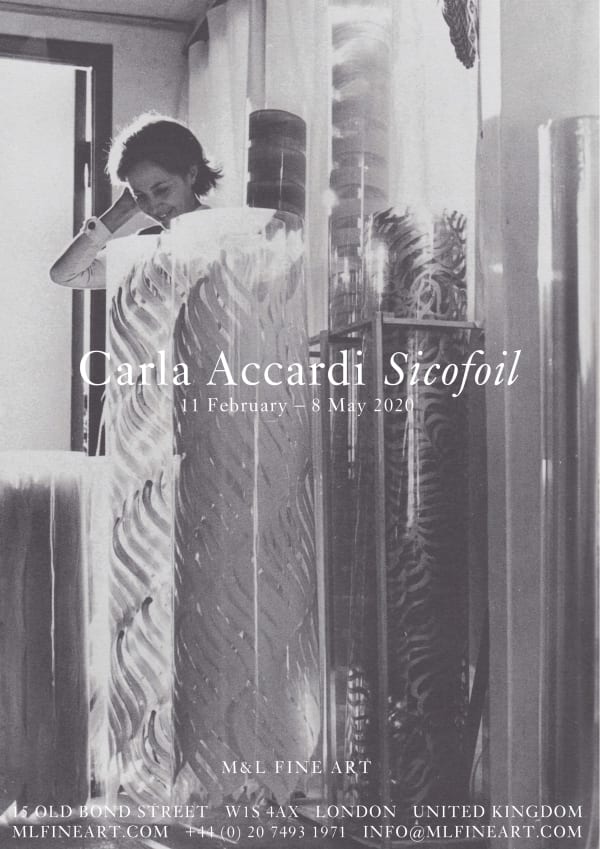

Carla Accardi: Sicofoil

11 Febbraio - 8 Maggio 2020M&L Fine Art presents a monographic exhibition showcasing Carla Accardi's seminal sicofoil works, featuring ten paintings from the 1960s and 1970s. This is the first solo presentation of the artist's...Maggiori informazioni -

Black & White: gesture and geometry in post-war abstraction

9 Maggio - 21 Giugno 2019M&L Fine Art is pleased to present a group exhibition of monochrome works by nine Italian and international post-war artists. Encompassing a range of mediums and techniques ranging from the...Maggiori informazioni

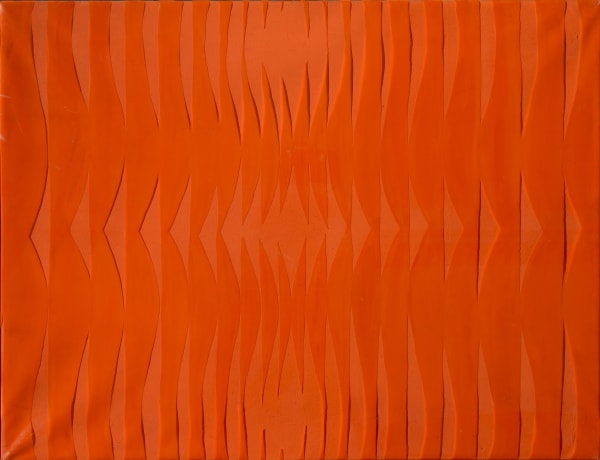

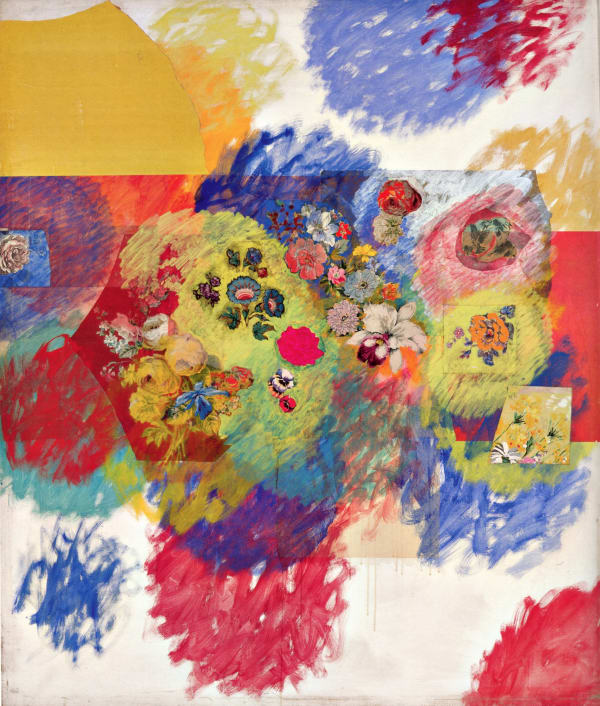

Born in Trapani, Sicily, in 1924, but Rome-based for most of her life, Carla Accardi is today acknowledged among Italy’s most important post-war artists. Over the course of a rigorous, poetic and conceptually informed career lasting nearly seven decades, Accardi developed a radical and sophisticated painterly syntax in which the formal and conceptual elements of style were made to embrace rather than conflict. Her paintings and installations made using sicofoil, a flexible, translucent plastic developed during Italy’s post-war industrial renaissance, were begun in 1965 and have since become the artist’s most iconic works.

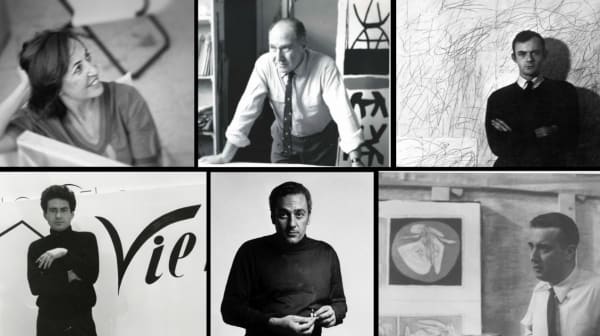

Following a brief period at the Accademia in Florence, where she met her future husband, painter Antonio Sanfilippo, Accardi moved to Rome in 1946. She and Sanfilippo immersed themselves in the young but ambitious art scene of Italy’s war-scarred capital, befriending fellow artists Ugo Attardi, Pietro Consagra, Piero Dorazio, Mino Guerrini, Achille Perilli, and Giulio Turcato. In 1947 this group, of whom Accardi was the only female representative, published the manifesto Forma, which, stating that “the terms Marxism and Formalism may not be irreconcilable,” argued for the legitimacy of abstraction in the fraught political climate of cold-war Europe. That same year in Milan, Lucio Fontana was among the signatories of the Primo manifesto dello spazialismo, further amplifying the choir of Italian artists hungry for recognition on the European scene.

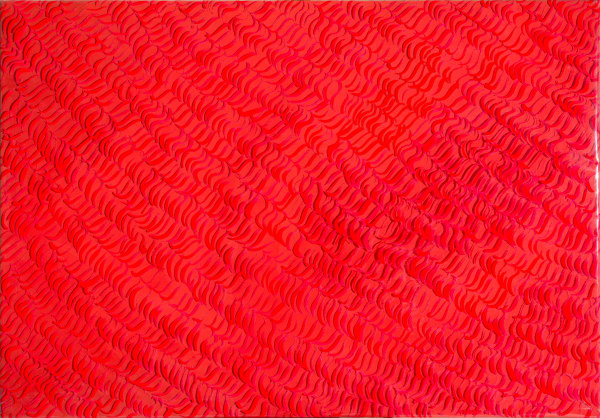

In the 1950s Accardi visited Jean Fautrier and Hans Hartung in Paris. The encounter with these two giants of Art Informel, pioneers in the development of new forms of experimental mark-making, influenced Accardi’s desire for a dialogue with the European neo-avant-gardes and simultaneously enlivened her research of an art made of pure signs. Her white-on-black compositions from this period are calm and controlled: dense forests of cyphers where white casein is constituted as a subject advancing in a contrasting territory, black. Negativity and positivity co-exist in a relation of mutual respect and reciprocal dependence.

From in 1959 onwards, the coloristic impetus in Accardi’s work gradually distanced her research from the anguish and post-war existentialism of Art Informel and Abstract Expressionism. At the same time, thanks to the efforts of influential critics Michel Tapié and Pierre Restany, and gallerists Luciano Pistoi and Gian Tomaso Liverani, Accardi’s work was shown in group and solo exhibitions in Paris, Rome, Osaka, Pittsburgh, Tokyo, Düsseldorf and London.

In 1963, Accardi’s dense clusters began to give way to configurations that gathered together signs and colours more loosely. Without assuming the inflexible and absolute nature of Giuseppe Capogrossi’s markers, or conversely giving way to broad chromatic fields, in the style of Clyfford Still, her marks acquired a form of indeterminate, repetitive seriality more attuned to the syntax of Mark Tobey, for example. Accardi’s informed exchanges with her American counterparts, including painters she met in Rome, such as Philip Guston, Mark Rothko and Jackson Pollock, are palpable. To the latter she was also bound by analogous working methods, for Accardi worked on canvases – and later sicofoil sheets – arranged on the floor of her studio, claiming her practice incompatible with easel painting. Compared to the convulsions of gesture and colour that marked the Abstract Expressionist’s work, however, Accardi’s was more oriented towards a process of engagement with pictorial identity, or an awareness of difference within the picture plane. The calm vitality and controlled radiance of her work led American critic Roberta Smith to claim that Carla Accardi is “the Agnes Martin of Italy.”

In 1964, Accardi, who had previously shown at the Venice Biennale in 1948, was again invited by Lucio Fontana, a supporter and influential mentor, to participate in Italy’s premier contemporary art exhibition. This resulted in a solo presentation curated by Carla Lonzi, the prominent critic and author through whom Accardi made contact with the Arte Povera group, especially Giulio Paolini, whose research also hovered over the limits of the picture plane, and Luciano Fabro.

In 1970 Accardi and Lonzi founded Rivolta Femminile, among the first feminist movements in Italy. With other members of the group, in 1976 Accardi created Cooperativa Beato Angelico, an experimental gallery space in Rome which, by presenting historic and contemporary female artists in dialogue, campaigned for the visibility of women’s art across centuries. The gallery’s inaugural exhibition, on April 8 of that year, centred on Artemisia Gentileschi’s Aurora and featured a substantial academic apparatus prepared by Accardi and her peers. It is worth mentioning that this was three years before Yvon Lambert’s seminal Mot pour Mot: Artemisia exhibition in Paris in 1979. Notwithstanding her deep friendship with Lonzi, Accardi later distanced herself from Rivolta Femminile’s militant ideology, remaining however a strong reference point for a generation of younger women artists in Italy and Europe.

Between 1970 and 1974 Carla Accardi spent long periods in Morocco, moving between Casablanca, Fez and Tangier. Through her association with gallerist Pauline de Mazières, she was introduced to the inner circle of international artists, writers and intellectuals who after the war to adopted Morocco as their home. Accardi’s encounter with Islamic culture and its art left a profound impact on her work, further deepening her engagement with an aesthetic of pure signs, and infusing new meanings to some recurring imagery within her practice, such as her tents and environments.

In 1986 Accardi was invited by curator Jan Hoet to Gent, Belgium and alongside forty-nine other international artists participated in the exhibition Chambres d’amis, presenting a 1971 large-scale sicofoil work. Developed across fifty-nine homes in the Flemish town, this extraordinary project matched artists – mostly conceptual practitioners such as Marisa and Mario Merz, Lawrence Weiner, Bruce Nauman, Daniel Buren and Joseph Kosuth – with homeowners who agreed to host the artists’ work and allow access throughout the summer, as in a delocalized museum exhibition. Responding to long-standing trends in advanced artmaking, which, in the words of the curator caused “painting to break loose from its frame and the canvas to be cut into bits,” this exhibition further validated Accardi’s research in yet another highly specific context, bringing together Italian and foreign artists in an original arrangement not unlike Harald Szeemann’s When Attitudes Become Form eighteen years earlier.

Starting in the 1980s Accardi shifted her research to another uncharted territory, once more laying bare the picture plane’s surface by exposing its rough, unprimed materiality. The transition from an art of transparency to one of overstressed opacity is another of example of the conceptual elasticity at play in the Accardi mature work, now caught in the wave of Neo-Expressionist tendencies rapidly expanding across Europe. Intermingling with resonances of Matisse’s sinuous late style, Accardi established contact points with the pictorial strategies of Transavanguardia through fellow Italians Enzo Cucchi and Francesco Clemente, in addition to Giorgio Griffa, and Georg Baselitz and Sigmar Polke in Germany, among many more contemporaries.

Carried by this ulterior gust of wind, Accardi’s work acquired even further institutional solidity throughout the 1990s, both in Italy and abroad. A major solo exhibition at Castello di Rivoli was followed by her inclusion in a series of pivotal group presentations in New York, curated by Germano Celant at The Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum and Achille Bonito Oliva at P.S.1 Contemporary Art Center. In 2001, Carolyn Christov-Bakargiev staged another show, focused on Triplice Tenda, at P.S.1.

Until her sudden death at age eighty-nine, in 2014, Carla Accardi continued to challenge the boundaries of the artistic territories she inhabited. Whether reconfiguring her own works, or variously alternating between opaque and translucent surfaces, in two and three-dimensions, Accardi’s practice continued to shape painting “in the manner of Ariadne’s thread, which is bound up with changing one’s awareness of oneself.”

-

miart 2025

3 - 6 Aprile 2025We are pleased to announce our participation at Miart 2025. On this occasion our booth will showcase a selection of historically relevant paintings, sculptures and...Maggiori informazioni -

TEFAF Maastricht 2025

13 - 20 Marzo 2025We are looking forward to seeing you at TEFAF Maastricht 2025! On this occasion our booth will showcase a selection of historically relevant paintings, sculptures...Maggiori informazioni -

Arte in Nuvola 2024

BOOTH B30 - C29 21 - 24 Novembre 2024ML Fine Art is pleased to announce its participation to Arte in Nuvola 2024, that will take place in Rome from 21 to 24 November....Maggiori informazioni -

TEFAF Maastricht 2024

7 - 14 Marzo 2024We are looking forward to seeing you at TEFAF Maastricht 2024! On this occasion our booth will showcase a selection of historically relevant paintings, sculptures...Maggiori informazioni

-

MIART 2021

17 - 19 Settembre 2021ML Fine Art is pleased to announce its participation to the 25th edition of Miart, Milan’s international modern and contemporary art fair, that will take...Maggiori informazioni -

NOMAD 2021

8 - 11 Giugno 2021ML Fine Art is pleased to announce its participation at NOMAD ST. MORITZ 2021, with a selection of works by Carla Accardi, Alighiero Boetti, Antonio...Maggiori informazioni -

Masterpiece London 2019

27 Giugno - 3 Luglio 2019M&l Fine Art is pleased to participate, for the fourth consecutive year, at Masterpiece London. Our booth featured a selection of historic works by Modern...Maggiori informazioni -

Artefiera 2019

1 - 4 Febbraio 2019Galleria Matteo Lampertico is pleased to partecipate at Artefiera 2019. Our booth will present a selection of works by Italian artists, including Carla Accardi, Angelo...Maggiori informazioni

-

MIART 2018

13 - 15 Aprile 2018Galleria Matteo Lampertico is pleased to partecipate at Miart 2018. Our booth will present a selection of works by Italian and Internartional artists, including Alighiero...Maggiori informazioni -

Artefiera 2018

2 - 5 Febbraio 2018Galleria Matteo Lampertico is pleased to partecipate at Artefiera 2018. Our booth will present a selection of works by Italian artists, including Alberto Burri, Carla...Maggiori informazioni

-

From Word to Sign

Accardi Basquiat Boetti Capogrossi Kounellis Novelli Perilli Twombly Luglio 14, 2020ML Fine Art - Matteo Lampertico invites you to discover our online exhibition, curated by Maria Albani, focused on the relationship between painting and writing,...Maggiori informazioni -

Conversations on Accardi: Episode 3

Laura Cherubini in Conversation with Matteo Lampertico Maggio 17, 2020On May 17, 2020, Matteo Lampertico, director of ML Fine Art, was joined by Laura Cherubini on Instagram Live for a conversation on the artist...Maggiori informazioni -

Conversations on Accardi: Episode 2

Hans Ulrich Obrist in Conversation with Pietro Pantalani Maggio 11, 2020On May 12, 2020, Pietro Pantalani, coordinator of the exhibition 'Carla Accardi: Sicofoil,' was joined by Hans Ulrich Obrist on Instagram Live for a conversation...Maggiori informazioni -

Conversations On Accardi: Episode 1

Flavia Frigeri in Conversation with Pietro Pantalani Maggio 3, 2020On May 3, 2020, Pietro Pantalani, coordinator of the exhibition 'Carla Accardi: Sicofoil,' was joined by Flavia Frigeri on Instagram Live for a conversation on...Maggiori informazioni